Years after having dramatically downsized my library (which I’ll talk more about some other time), I’m finding myself frequently looking at what remains of it and feeling puzzled by past choices. One of the most puzzling is my lost collection of books by and about Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury group, which I don’t recall consciously deciding to give up. And yet all that remains on my shelves are two of Woolf’s novels — To the Lighthouse and Mrs. Dalloway (that rare case of my having fallen in love with a book I was assigned in high school), both in stuffy, unread, navy-blue clothbound editions, you know the ones — and a well-thumbed, sun-faded paperback of A Moment’s Liberty: The Shorter Diary (out of print), which according to the post-it bookmark still adhered to page 169, I left off at the entry for 15 October 1923. Probably fifteen or more years ago.

Gone are Virginia’s other novels, the biography, Leonard Woolf’s multi-volume autobiography, various other books of their circle — books I had acquired and been given. Did I ever own the rest of VW’s diary (i.e., the complete five-volume set), or at least Leonard’s edit, A Writer’s Diary? And the letters? I no longer know. But while countless other books have gone unmissed, the Woolfs feel a bit like a phantom limb. A phantom shelf, you might say.

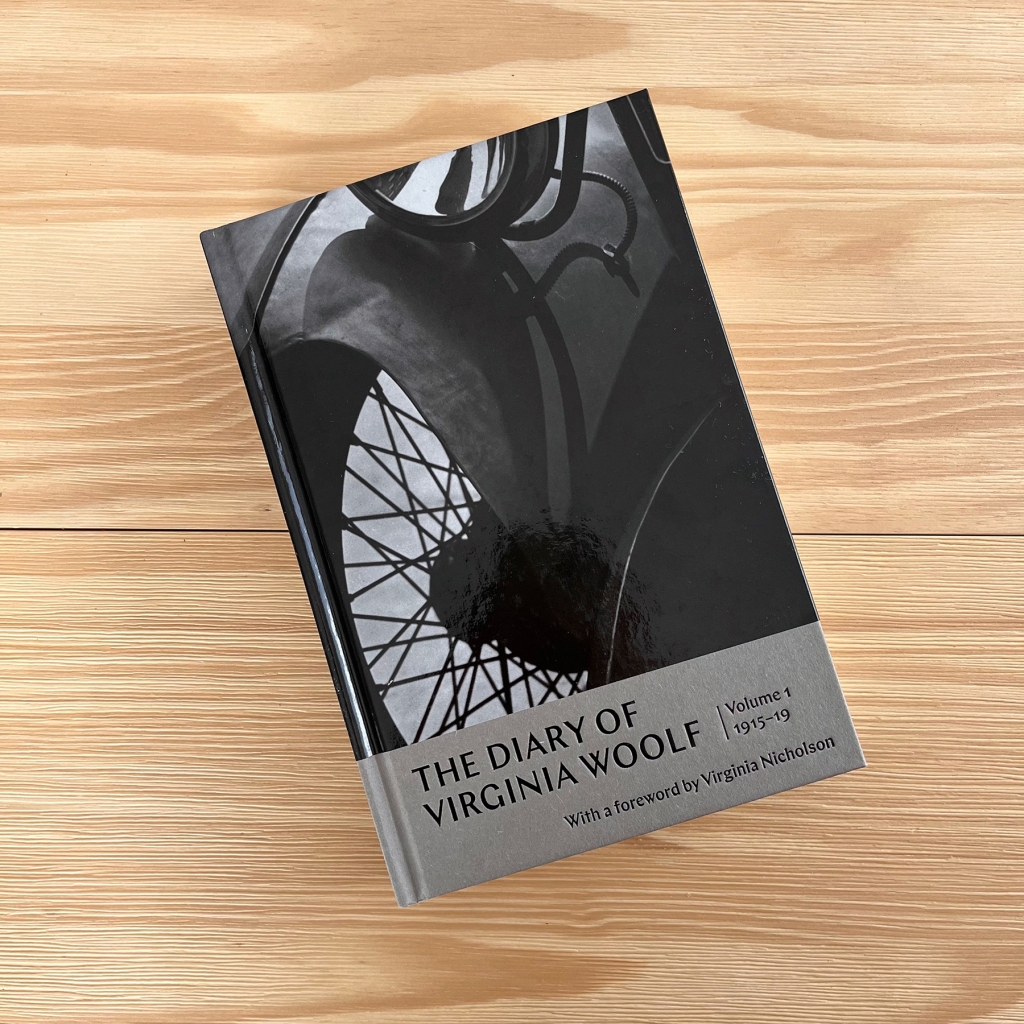

Wandering through Instagram one day last week I saw a mention of a book that’s about to be published in the UK called Rural Hours: The Country Lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Rosamond Lehmann, by Harriet Baker. In Baker’s feed there is mention of a piece she had written for the Paris Review last summer called Virginia Woolf’s Forgotten Diary, about the ‘Asheham Diary,’ which I knew nothing about — it’s neither included nor mentioned in the Shorter Diary. Baker’s essay is gorgeous, but also it’s how I learned that Granta has reissued the entire diary in five shiny new hardcover volumes, which contain the full Asheham Diary for the first time. Resisting the urge to eat mac and cheese for the next month and order the full set, I bought Volume 1.

Here’s how Asheham fits in:

The 1915 Diary

On 1 January 1915, living at 17 The Green, Richmond (outside London), with her husband Leonard, Virginia started a diary that she kept until 15 February. Each day she wrote a paragraph or two about their day — who they saw or wrote to, or ate with, where they went, what they were working on. In his introduction to the original set, her nephew (and biographer) Quentin Bell sets the stage, like a Masterpiece Theater host:

“Virginia was living in a kind of vacuum and was still barely recovered from her [second] bout of insanity. Since she did appear to be getting well again and was able to work and to enjoy Leonard’s company [they married in 1912] she may be considered happy. But in other ways her state was not enviable; she had reached middle life without any great achievement to her credit [she was 32!], and all around her were younger people rapidly advancing towards fame. She was poorer than she had ever been. She almost certainly knew that her mental health was precarious. She had hardly begun to find the fictional form that suited her, the great literary adventure of her life still lay unseen in the future, and she awaited with dreadful anxiety the publication of her first novel.”

That novel, The Voyage Out, is alluded to only once, in passing, in the diary of the year it was published. As noted, this diary only lasted until mid-February — before the end of that month she had another mental breakdown.

The Asheham Diary (1917-18)

Recuperating at her rural Sussex rental, Asheham House, and finding a semblance of normalcy again, she made notes in a pocket-sized notebook from 3 August to 4 October 1917, at which point the Woolfs resumed life in Richmond. That much was always included in the “complete” set of the diaries, but she wrote in it on future visits to Asheham, later in the year and into the next. Those remaining entries are what’s newly included — as Appendix 3 — in the first volume of the Granta reissue.

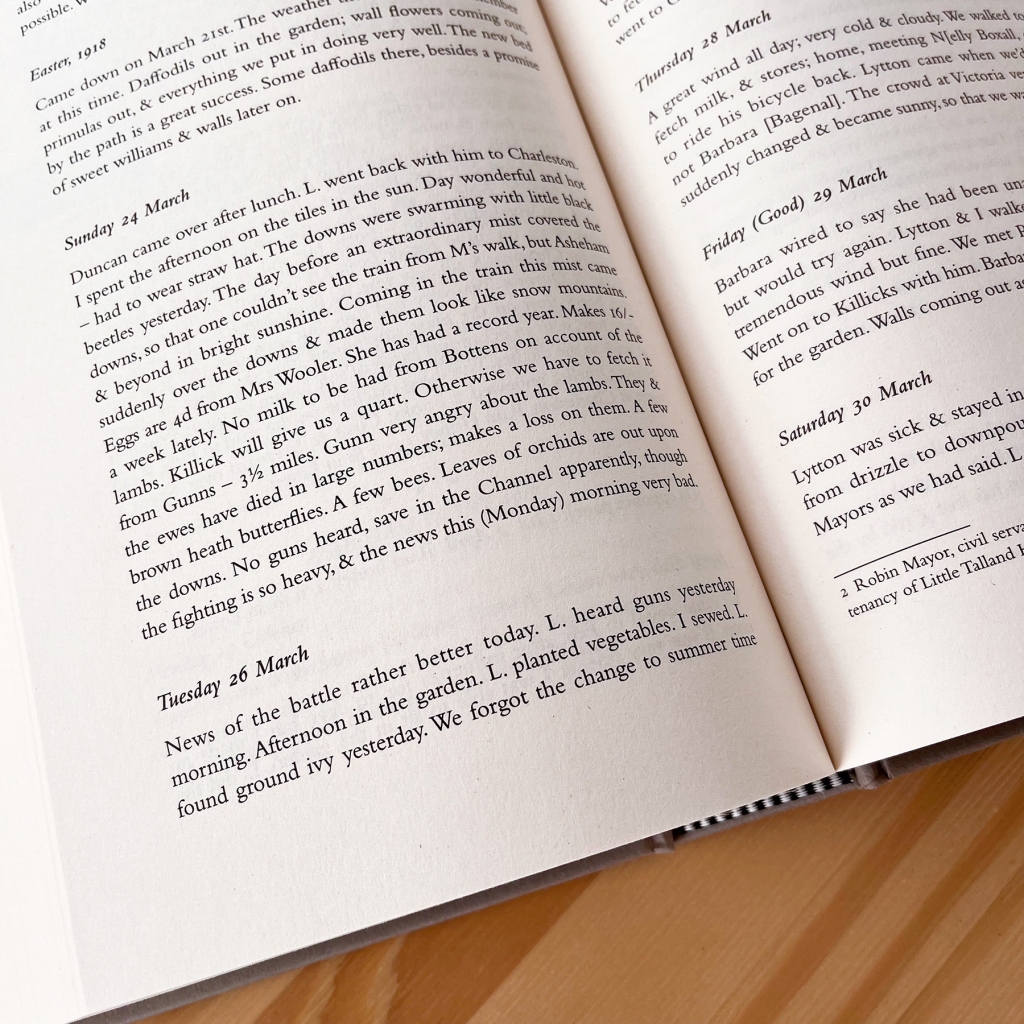

The entries she made in this smaller diary are generally much shorter and more note-like (pictured above). The war is even more felt, and the notes are often about the price of eggs — literally, she keeps track of how much she paid to whom — as well as the things they can’t get due to rations or scarcity. They walk, bicycle or take the train wherever they go, and frequently forage for mushrooms and blackberries, often coming up empty. She remarks that she couldn’t go to social events if she wanted to because her clothes are all too shabby. She isn’t writing this diary, she (for the most part) is simply recording facts and visitors, weather and expenses, what’s blooming or hatching or molting (and even a laundry list, not published), but it is no less a compelling picture of the time and her state. And as Baker notes, there are anecdotes and imagery that reappear in her later novels.

The Main Diary (1917-1941)

Upon their return to Richmond, on 8 October 1917, she opened a new notebook and wrote: “This attempt at a diary is begun on the impulse given by a discovery in a wooden box in my cupboard of an old volume, kept in 1915, & still able to make us laugh at Walter Lamb. This therefore will follow that plan — written after tea, written indiscreetly, & by the way I note here that L. has promised to add his page when he has something to say. His modesty is to be overcome. We planned today to get him an autumn outfit in clothes, & to stock me with paper & pens. This is the happiest day that exists for me.” And then she describes the rest of their day in the remainder of the one paragraph: it rains; they go for an errand-walk around London, with observations about a fellow shopper; they visit Dr. Johnson’s house (by then a museum); and while dropping off a review she’d written for the Times Literary Supplement, they also trade some gossip. She would keep up this diary — which altogether spanned 30 notebooks — until her suicide in 1941.

It is indiscreet and gossipy and occasionally outright horrifying, the things she says. It’s also a remarkable window on a fiercely intelligent couple and their friends and family, many of whom were highly influential, boundary-breaking figures at a key time in European history. It is constantly both ordinary and extraordinary in that way. I think what I had decided all those years ago was that the Shorter Diary would be enough for me and I could always read the longer one if I felt unsatisfied at the end of that, which, as noted, I never got to. Reading them side-by-side now, I’m happy to have both the yearly introductions in the shorter and the extensive footnotes in the longer.

In her preface to the original 1977-84 five-volume set, Anne Olivier Bell (Quentin’s wife, known as Olivier) — whose editing and annotating of the diaries is itself a masterwork that took her ten years — wrote “Virginia Woolf’s interests and observations range over so wide a field — art, literature, politics, people, and her surroundings — that some supporting explanation seems necessary. In deciding how much annotation is appropriate, I have to take into account the probability that — for reasons of cost and copyright — there is not likely to be another edition of these diaries for perhaps half a century.” At that point Leonard had already published his edit (in 1953), and Olivier’s “Shorter” edit would publish in 1989. But she was almost exactly right that it would be 50 years before another complete set would be produced. And here we are. Hopefully there will be a US edition. I could only find the new Granta hardcovers in the US at Amazon, and I hope I can justify buying the next and the next by finishing them one at a time before they go out of print. Meanwhile, perhaps someone will also publish updated hardcovers of the two edited versions. But I’ll be hanging onto my worn copy of A Moment’s Liberty regardless.

As I’m writing this, on Sunday March 24th, I turned to the final page of the shorter diary — and confirmed online that it is indeed the final entry — to see what Virginia’s last sentence was. (You can see it in her handwriting here.) It was four days before she drowned herself in the Ouse. The last sentence: “L. is doing the rhododendrons …” The date: March 24th.

[ IMAGES: Photos © Karen Templer of The Diary of Virginia Woolf: Volume 1, 1915-19, published by Granta in 2023 ]

2 responses to “Virginia Woolf’s diaries, lost and found”

I also read and loved To the Lighthouse and Mrs Dalloway at school. They made me consider an English Lit degree but I chose Psych. instead and have worked for many years in Crisis mental health and suicide prevention . I haven’t delved much into VW’s MH struggles but I do know that whilst suicidal thoughts can be with someone constantly, deciding to act on those thoughts can be very spontaneous. It doesn’t surprise me that VWs last entry was so mundane – perhaps she didn’t know it was her last entry.

on a lighter note, all my diaries have faltered due to being boring – now I realise even the great writers wrote boring diaries!

LikeLike

I haven’t read the later years but I believe the consensus is that she knew it was coming for her again and that she wouldn’t be able to beat it again

LikeLike